Stylish Women’s Purple Leather Blazer Jacket with Two Buttons

$279.00 Original price was: $279.00.$179.00Current price is: $179.00.

- Premium Purple Leather Material

- Two-Button Closure for a Chic Look

- Slim Fit with Tailored Design

- Suitable for Casual and Formal Wear

Introducing the Stylish Women’s Purple Leather Blazer Jacket with Two Buttons, an elegant fusion of classic design and modern flair. Crafted from premium leather, this blazer offers a timeless silhouette that seamlessly complements any wardrobe. Whether you’re dressing up for a business meeting or adding a touch of sophistication to your casual wear, this blazer serves as the perfect statement piece. The rich purple color adds a bold, yet chic touch, while the two-button closure enhances the structured look. Embrace confidence and style with this versatile jacket from MotoCollection, designed to make every outfit stand out.

Specifications:

- Premium Purple Leather Material

- Two-Button Closure for a Chic Look

- Slim Fit with Tailored Design

- Suitable for Casual and Formal Wear

- Soft, Luxurious Feel for Comfort

- Available in Multiple Sizes

- Durable and High-Quality Craftsmanship

- Stylish and Bold Color for Statement Looks

Elevate your wardrobe with the Stylish Women’s Purple Leather Blazer Jacket. Shop now at MotoCollection and make a lasting impression with this stunning piece. Don’t miss out—add this must-have blazer to your collection today!

| Color |

Black ,Dark Brown ,Medium Brown ,Russet ,Vintage Black ,Vintage Brown ,Your choice |

|---|---|

| Gender |

Women |

| Size |

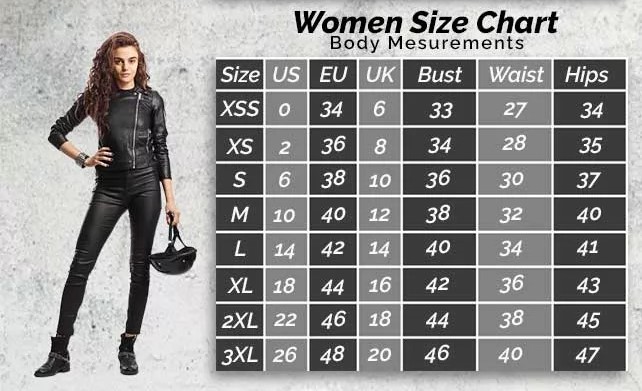

S ,M ,L ,XL ,2XL ,3XL ,4XL ,5XL ,6XL ,Custom |

3 reviews for Stylish Women’s Purple Leather Blazer Jacket with Two Buttons

Popular products

12 Gauge Men’s Leather Vest for Motorcycle Riders

13 Reasons Why Justin Foley (brandon Flynn) Jacket- Dylan Minnette

1950s Motorcycle Black Leather Jacket

1965 Minnesota Twins Varsity Blue Wool Jacket

1990 Stussy International Tribe Wool & Leather Red Vintage Varsity Jacket

8 Ball 90s Black Vintage Bomber Jacket

8 Ball 90s Style White Bomber Jacket

8 Ball Bubble Parachute Jacket

8 Ball Logo Fur Hooded Parka Leather Jacket

8 Ball Logo Printed Red Fur Jacket

8 Ball Logo Red Black and White Bomber Jacket

Elias (verified owner) –

I received my order earlier than expected!

Emma Louise (verified owner) –

Great experience! The leather quality exceeded my expectations.

Sophia Grace (verified owner) –

The custom design process was easy and seamless.